Alienation as a concept was first formulated by sociological thinkers of the 19th century, but it perhaps applies even better to the 20th and early 21st centuries. The factory system, which Marx had in mind when he formulated his ideas about alienation, has declined in economic importance and the percentage of the workforce in Western societies that it employs since the late-20th century shift to a “knowledge economy” at the top and the service sector lower on the income ladder. However, anomie (as described by Durkheim) has continued to be a frequent condition in modern society, and bureaucracy (Weber’s primary focus) has only grown in importance. Thus, a reevaluation of these conceptions of alienation in the context of modern society is warranted.

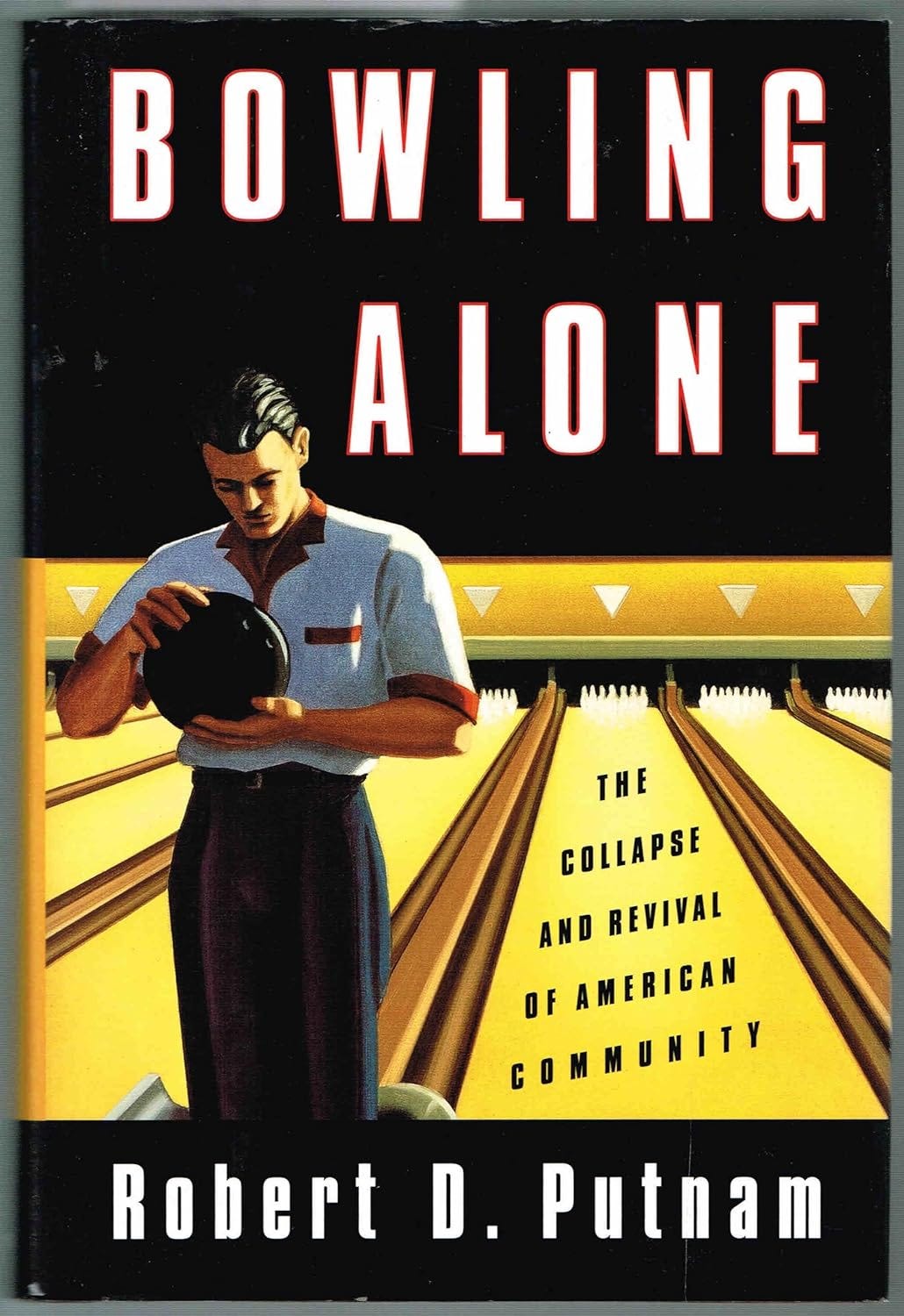

One of the most influential sociology texts of the last few decades is Robert Putnam’s 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. While Putnam does not directly address alienation per se, he focuses on a concept that could be thought of as its opposite: social capital, defined as social connections and trust between people. He argues that social capital has undergone a precipitous decline from the 1960’s onward, with Americans becoming increasingly distant from, and more distrustful of, one another. Putnam asserts that besides making America a lonelier place to live, this change is making us less happy, safe, healthy, wealthy, and satisfied with the political system.

A large section of Bowling Alone is devoted to describing why this erosion of social capital is happening. The time pressures of modern life, and economic hardships (real or perceived) may be minor contributing factors, but the data seem to indicate that they are not the main causes. Neither is the rise of women in the workforce and the accompanying increase in single-parent families. However, the rise of suburban “lifestyle enclaves” and “gated communities” have isolated Americans not only from those different from themselves (a decrease in “bridging” social capital), but also (paradoxically) from those similar to them. Suburbanization has also led to longer commutes-reducing the time available for social interactions-and disrupted the sense of well-defined community once found in small towns where everyone knew everyone and left their doors unlocked.

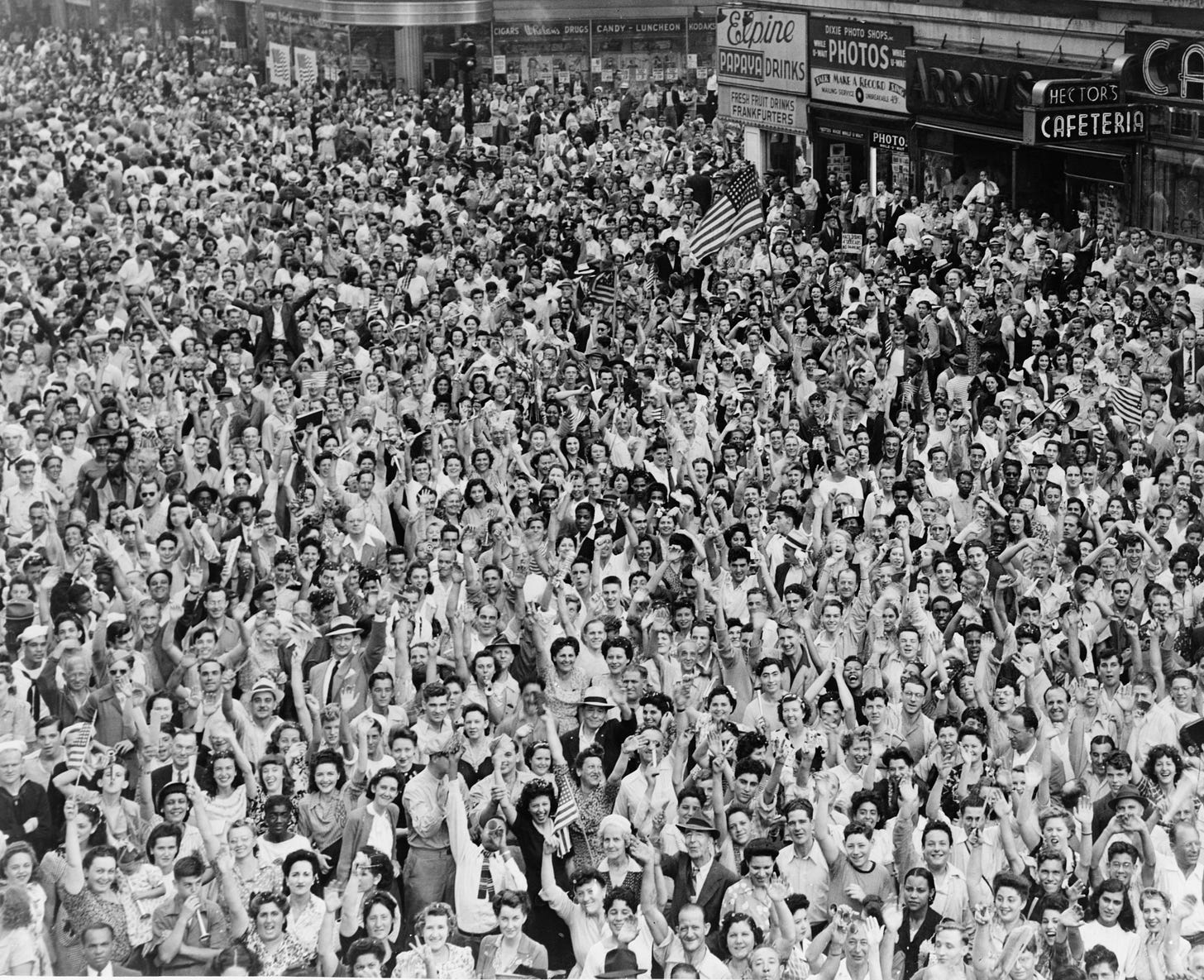

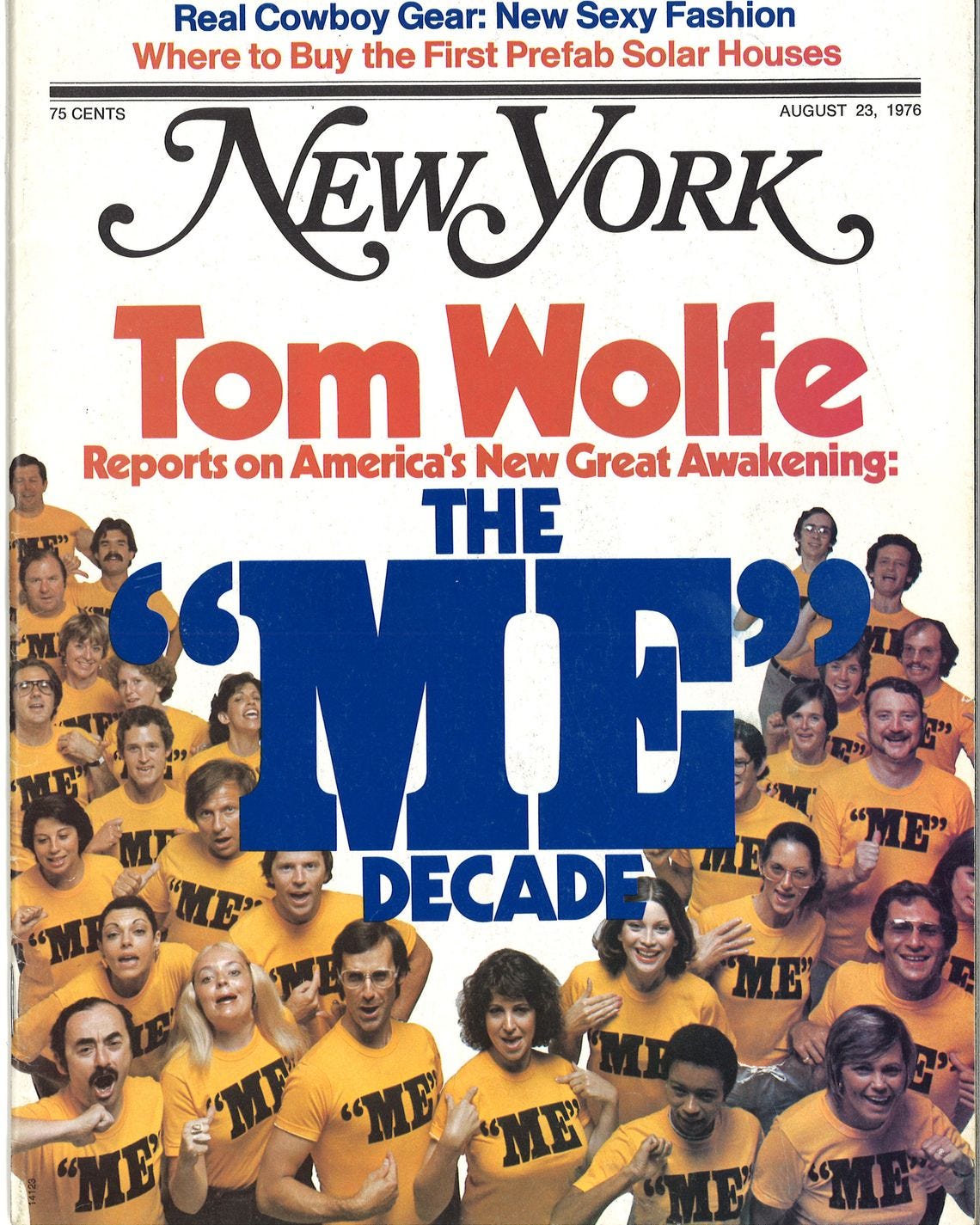

The single most important reason Putnam targets as the cause of civic disengagement is generational change. As the “long civic generation” born roughly between 1910 and 1940 is replaced by the baby boomers, Generation X’ers, Gen Y’ers (Millenials), and, presumably, Gen Z’ers, social capital has declined. The likeliest explanation for why the civic generation is so much more engaged than their children (and even their parents) is that they came of age during, and in some cases directly participated in, World War II. This war generated a strong sense that whether you were a man, woman, or child, you needed to pitch in to help the war effort. This “rally-round-the-flag” effect led to a massive boom in volunteer involvement which, for those who participated in it, continued even after the war. Later generations have been statistically shown to be less community-focused and more individualistic than the Greatest and silent generations. The baby boomers did not achieve cultural prominence in the 1960’s, as is commonly thought (a myth perhaps perpetuated by the boomers themselves). Most of the famous young artists, thinkers, and activists of the 60’s were actually members of the silent generation (just in the realm of popular music, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Simon & Garfunkel, and all four Beatles were born before 1945). The years that most typify the boomers were the 1970’s, what journalist and author Tom Wolfe famously described as the “Me” decade, in reference to the boomers’ increased focus on their own neuroses, personal problems, and self-realization (Wolfe, 1976).

Another possible cause for Americans’ civic disengagement (one which is partially correlated with generational effects) is technology, specifically with regards to mass media. The main aspect of this that Putnam focuses on is television. Overall, television seems to have a negative effect on social capital. The more television people watch on average, the less likely they are to be involved in community organizations, politics, clubs, and church; they even spend less time with relatives. Not all television programming is created equal, however: watching news programs and educational television is, in fact, positively correlated with civic involvement. Unfortunately, most other television is not, and news viewership is decreasing as younger generations are less likely to watch news programs than older audiences. The reasons why television watching reduces social engagement seem to be threefold: because it cuts into time that might otherwise be spent engaging with fellow humans; because television watching can be compulsive, bordering on addiction; and because most television programs (and the advertisements in between) encourage sloth, materialism, and disengagement from community.

Television watching has permeated society during the twentieth century. However, amount and style of viewing varies by generation. The civic generation watched the least television, and were also the most likely to be selective viewers who only tune in when there is a specific program they wish to watch, compared to channel surfing generations such as the boomers and Gen X’ers who spend much more time with the “tube” on, whether or not they are actively watching it. As the civic generation has died out, Americans have watched more television; in 1950, the average American household spent a bit more than four and a half hours watching television, while at peak television viewership in 2009-2010, the average American household watched almost nine hours of television a day (Madrigal, 2018). Television viewing has actually decreased over the past decade, although Americans still watch about as much television as we did in the early 2000’s. This decrease in television watching is probably due to generational trends which now run counter to those of two decades ago. Young people currently watch less television (narrowly defined) than older people (“Television Is Still”). This is probably due to competition from other types of screens, such as computers, smartphones, and video-gaming consoles, many of which are connected to the Internet; granted, much of this other screen time may be spent streaming television programs or other video content.

As the Internet becomes increasingly integrated into the lives of Americans (particularly young ones) it is almost indisputable that it will affect our social patterns in some way. Therefore, whether this shift will increase, decrease, or have no effect on social capital is an important question. In his discussion of Internet usage, Putnam suggests that the Internet complements face-to-face communication, and that solely virtual communications probably allow for casual social interactions, but not the creation of deep bonds. This is borne out by a cursory examination of the current status of the Web. There remains a sharp distinction between friends you have met in person and Facebook “friends” whom you probably don’t know very well. Unfortunately, the early study he cites which says that extensive usage of the Internet leads to social isolation and depression also seems to have been correct. The Monitoring the Future survey has found that teens who spend more time looking at screens are also more likely to be unhappy and depressed (Twenge, 2017). Much of this seems to stem from loneliness caused by social media usage, which would at first glance seem to connect people more, and in many cases does so. However, it can also exacerbate teens’ (and some non-teens’) fear of missing out. Internet use is also almost as much of a time suck as television, if not more of one. Over the last fifteen years in particular, there has been a precipitous drop in the amount of time teenagers spend with their friends in person. The decline in these informal social connections seems bad news for America’s already much battered stock of social capital—if some teens hardly even engage with each other as friends, there seems little hope that they will engage with one another as citizens.

But what of those who use the web for applications such as reading the news or discussing politics? The difficulty of studying this type of Internet usage is the many ways of engaging in these seemingly more prosocial activities that the Internet provides. The social impact of reading an article from The Washington Post or The New York Times or watching a video from NBC or CBS News on the web is probably not significantly different from that of the print or broadcast versions. However, most people who get the news online get it through social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or (more recently) even TikTok. To say that these sources of information are not always reliable is an understatement. On these sites truth and falsehood is mingled in a constant competition for clicks, and it takes a savvy news consumer to tell the difference. Similarly, political discussions online range from intelligent, reasoned debates to bitter “flame wars.” However, the Internet has also been used to organize real-world social activism such as school climate strikes or the “March for Our Lives.” This is accompanied by the encouraging statistic that more young people now describe themselves as politically engaged than just a few years ago (Deal, 2019). In addition, political campaigns have begun to reach out to voters through social media. Thus, the Internet seems to have a mixed impact on social capital, leading to almost unparalleled disengagement from peers and even to mental health issues, but at the same time becoming a platform for renewed activism and political engagement. As with many technologies, the social impact probably stems less from the thing itself than from the uses to which humans put it.

Karl Marx blamed alienation on modern capitalist society, which dehumanizes workers by treating them as machines, and also alienates workers from each other by making them competitors rather than collaborators. This description fits many modern jobs well, from flipping burgers at fast-food restaurants to fulfilling orders at an Amazon warehouse. However, this dehumanization may result from more than employment. Modern capitalism treats humans not only as workers, but also as shoppers. The United States of America is a highly consumerist society, in which we are constantly bombarded by commercials. One of the most important ways in which companies now advertise their wares to us is through television programming. As noted earlier, this may be one of the reasons for television’s antisocial effects. Through television, capitalism has infiltrated our leisure time as well as our jobs.

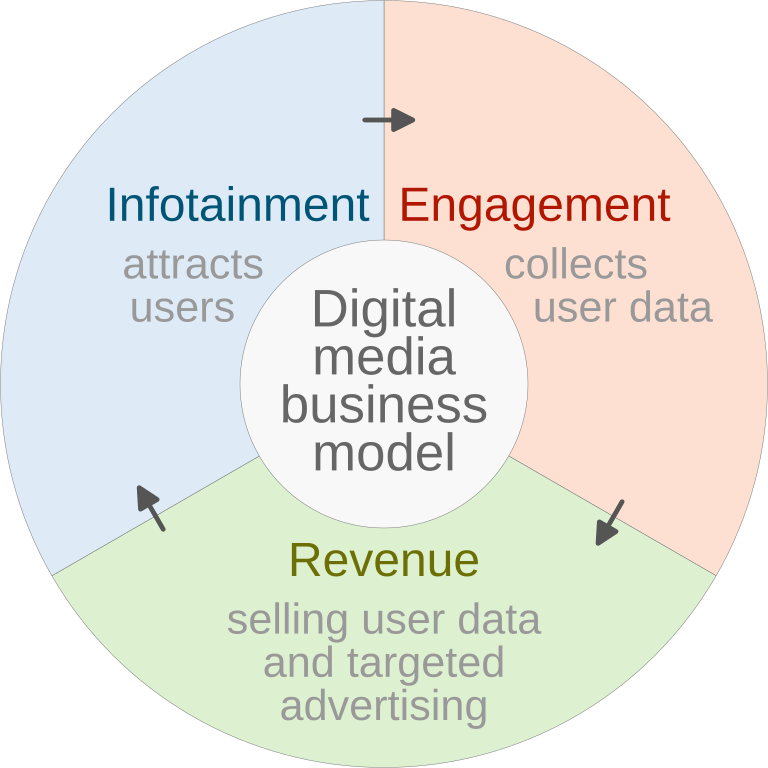

However, alienation takes on another dimension as more of our free time is spent online, especially on social media. Besides “sell[ing] ads” as Mark Zuckerberg put it, social media companies also make money by collecting data from their users and selling them to data farms, which in turn resell these data to advertising agencies and other firms. Thus, whether we know it or not, social media turns its users into not only “eyeballs” to be advertised to, but also into unpaid workers—or even products—who generate revenue for the social media and data collection companies. Social media can also alienate us from other human beings by pitting us against one another. The things we post on social media are in implicit, if not explicit, competition for “likes,” “shares,” and “views.” Not getting enough virtual attention on a post could lead to feelings of exclusion and depression; seeing someone else’s post getting more likes could lead to resentment. Even some social media companies seem to recognize this as a problem—or at least that others believe it to be: Instagram, for example, has tested hiding other users’ like counts. Unfortunately, no such quick, simple fixes will solve the modern media environment’s alienating and antisocial influence. Increasing social capital will not simply happen. If we want to restore our engagement with our fellow citizens, we must make a conscious and concerted effort to reshape our society, even if it leaves us with less to do while waiting in line at StarbucksTM. Perhaps we’ll just have to talk to our fellow humans?

Bibliography

Deal, J. (2019, November 18). Youth Political Engagement and Hope Ahead of the 2020 Election. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from https://harvardpolitics.com/united-states/youth-political-engagement-and-hope-ahead-of-the-2020-election/ [dead link; archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20191220161757/https://harvardpolitics.com/united-states/youth-political-engagement-and-hope-ahead-of-the-2020-election/ ]

Madrigal, A. (2018, May 30). When Did TV Watching Peak? Retrieved February 4, 2020, from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/05/when-did-tv-watching-peak/561464/

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Television is Still Top Brass, But Viewing Differences Vary With Age. (2016, July 18). Retrieved February 4, 2020, from https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2016/television-is-still-top-brass-but-viewing-differences-vary-with-age/

Twenge, J. M. (2017, September). Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? The Atlantic, 320(2), 58-65. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/09/has-the-smartphone-destroyed-a-generation/534198/

Wolfe, T. (1976, August). The “Me” Decade. New York, 9(34). https://nymag.com/article/tom-wolfe-me-decade-third-great-awakening.html