Kennedy (1983) Part 2: “I have a rendezvous with death…”

In the fifth episode, Kennedy decides to send military advisors to Vietnam, but thinks the military’s suggestion of sending combat troops to solve a political problem is stupid, discussing how South Vietnam is rife with prostitution, disease, and repression by Ngô Đình Diệm’s secret police. He dispatches Lyndon Johnson, Stephen Smith (an almost unrecognizably young Kelsey Grammer, a year before he debuted as Dr. Frasier Crane on Cheers), and Jean Kennedy Smith to visit Asia; JFK instructs Johnson to listen to what Diệm needs.

John and Jackie discuss the book Portrait of a President by William Manchester, with John objecting that he is not St. Augustine, or any of the ancient leaders Manchester compares him to. Kennedy and his staff watch the televised broadcast of the launch of Freedom 7, piloted by Commander Alan Shepard, who became the second human and first American in space.

After hearing from Smith and Johnson, Kennedy begins to grow worried about becoming entangled in Vietnam and doesn’t want to send ground forces there. Hoover claims to Robert that the American Communist Party is a menace but that organized crime and the mafia do not exist in the United States; Robert tells Hoover there need to be more black FBI agents, but Hoover says that will never happen while he is commissioner and hints that he knows things about the president. John and Jackie travel to Europe, visiting Charles de Gaulle in Paris, meeting with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, and seeing Queen Elizabeth, Prince Phillip, and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in London; Jackie seems even more popular than John. Hoover gathers evidence of a Kennedy mistress and her other male “friends,” and then tells Robert that the president has been “dangerously indiscreet.” Bobby tries to make Jack understand the seriousness of the situation and that Hoover might plan to confront Jack with any dirt he might have on him. Jack tells Robert to let Hoover bug Martin Luther King, since Bobby is sure Hoover won’t find anything incriminating. Joe Sr. has a stroke while golfing and is rushed to St. Mary’s Hospital in Palm Beach; this leads to one of the most touching scenes in the series, in which Jacqueline tells her stricken father-in-law, who is unable to move or speak, that he is one of only three men she has loved, because he made her feel like a part of the family.

The episode closes with two contrasting Christmas celebrations: Hoover has dinner with an FBI agent (Rick Warner), perhaps meant to represent his second-in-command (and possible sexual or romantic partner) Clyde Tolson, and they exchange gifts, with Hoover receiving a book he already owns and giving to the Tolson stand-in a film reel containing “the outstanding movie G Men…with a great performance by Mister James Cagney.” The Kennedys, by contrast, have a busy and boisterous family dinner presided over by Rose and John in Joe Sr.’s absence; after Rose offers a prayer, and John cuts the Turkey, he brings a note of solemnity by noting that James Thomas Davis had become the first American combat casualty in Vietnam three days before.

Continuing to discuss the war after the meal, John and Robert are interrupted by the rest of the family arriving to open presents, and Jack delivers Bobby his “gift” by telling him that “the girl” has backed off.

The sixth episode begins with Hoover observing a pro-Castro, anti-Kennedy protestor outside the White House. Inside in the Oval Office, head of U.S. Steel Roger Blough (James Dukas) informs President Kennedy that they plan to raise steel prices $6 a ton, in defiance of an agreement the Secretary of Labor had recently negotiated between the United Steel Workers and the steel industry to keep both wages and prices down. Kennedy tells Blough this will likely lead to inflation, and is a patriotic issue. They are interrupted by a call from Jack’s mistress, begging him to get the FBI off her. Robert tells Hoover to investigate Bethlehem and U.S. Steel for price-fixing and anti-trust violations. John gives a press conference in which he criticizes the steel industry for a “wholly unjustifiable and irresponsible defiance of the public interest.”

Hoover’s agents receive a direct order from Robert to stop tailing the girl, and Hoover tells them to take the men off her for thirty seconds…then double the detail, and also interview journalists covering the steel industry in the middle of the night. Robert talks to Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin (Harry Goz) about potential anti-American activities emanating from Cuba, and Dobrynin states the Soviets have no intention of starting a war. At a party in D.C., John, Robert, and Lyndon discuss unusual Soviet naval movements and Raúl Castro’s visit to Moscow to meet Khrushchev, both of whom Johnson describes as “peasants,” while Ethel walks along the lip of a swimming pool before falling in.

After McGeorge Bundy (Albert Stratton) shows John F. Kennedy photographic evidence of Soviet missiles in Cuba, the remainder of the episode essentially becomes an abbreviated version of The Missiles of October. The main difference in the depictions is the presence of Lyndon Johnson in Kennedy, although interestingly enough his one major scene during the Cuban Missile Crisis is of John berating him for not offering ideas during EXCOMM meetings: “Don’t wait to be asked! If you think you have a solution then state it and let everyone else know as well. Don’t just sit here, for god’s sakes, nodding your head and pulling your ear!” Perhaps this indicates that his lack of presence in Missiles is because he had so little to say during the crisis that Bobby almost entirely left him out of his account of the event.

The final episode begins with the confrontation between John F. Kennedy and J. Edgar Hoover that has been building over the course of the series. Hoover tells Kennedy that the woman he has been seeing is intimate with the mafia (which he now apparently believes in the existence of) and that if John ceases all contact with her, any evidence Hoover has of the matter will be destroyed…when Hoover retires. Bobby, who was also in the room, tells Jack the affair has to stop, which Jack says it has; he tells Robert not to get the evidence, because “It’s like playing poker, and I think he’s bluffing…he’s only powerful in his way if he keeps his dirty secrets to himself. The hell with it.” Based on the information provided over the course of the series, that the woman referred to has visited the White House, called Jack from Chicago, and had relationships with mafiosi, one can infer that she is probably Judith Immoor Campbell, ex-wife of actor William Campbell (who would later play Trelane and Klingon Captain Koloth on Star Trek). In 1960, Frank Sinatra introduced her to both Kennedy and Chicago Outfit boss Sam Giancana, who in turn connected her with his associate John Roselli; both Giancana and Roselli were recruited by the CIA for attempts to assassinate Castro.

On May 3, 1963, Kennedy watches news footage of Birmingham police using fire hoses and dogs to attack civil rights protestors, including children. John wonders how he can bring a message of peace to Europe (where he is scheduled to travel) when there is so much violence at home. Nevertheless, travel to Europe he does, visiting West Berlin and delivering a speech in which he compares the proudest boast of the ancient world, “civis Romanus sum” [I am a citizen of Rome] to that of the modern, “Ich bin ein Berliner” [I am a Berliner]. (This has often been falsely stated to have been interpreted by his German audience as a humourous language error in which Kennedy called himself a jelly doughnut; however, this is not actually true, as actual residents of Berlin call this dessert pfannkuchen [pancake]. This joke actually derives from the 1983 spy novel The Berlin Game by Len Deighton). Back in America, at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivers his “I Have a Dream” speech at the foot of Lincoln’s statue at the Lincoln Memorial.

Jackie and Rose feed Joe Sr. at breakfast while discussing John’s birthday party, featuring Marilyn Monroe, with Ethel (although Marilyn was actually at his 1962 birthday gala, less than three months before her death), when Jackie starts to feel labour pains (in reality, she felt them while taking Caroline and John Jr. horse riding). On August 7, Jacqueline gives birth to Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, who has surfactant deficiency disorder (then called hyaline membrane disease), an infant respiratory condition caused by insufficient production of surface tension-reducing pulmonary sufactant, without which the alveoli of the lungs collapse under the pressure of the lung fluid.

Robert is telling John, Pierre, and Dave about a tense meeting with civil rights supporters when John is told his son is dead. A depressed Jacqueline decides to go to Greece, having been invited by shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, while John plans to stay at Hyannis Port over the summer; she gives him a St. Christopher medal to replace the one he put in Patrick’s coffin.

While sailing with Jack, Ted, and Dave, Bobby says he wants to leave the role of attorney general, but Jack tells him to stay because otherwise it will look like they are abandoning civil rights; Ted and Jack discuss the upcoming election (possibly against Barry Goldwater) and what Jack will do if he loses. While the children talk to their mother on the phone, Jack reads part of a speech about power and poetry to Joe Sr., which he will deliver at Amherst College on October 26, 1963. Jacqueline returns to America on October 17 and gives the children presents.

In November, Kennedy’s advisors discuss the recent coup in South Vietnam, in which Diệm and his brother Ngô Đình Nhu were captured, then repeatedly shot and stabbed in the back of an armored personnel carrier. Kennedy plans to recall Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., while Lyndon Johnson says he gave his word to Diệm that they would have US support and insists that they cannot lose Viet Nam, although John tells him “They’re gone now.” (Unmentioned is that the coup was CIA-backed; Cable 243 from the State Department to Lodge stated that it was not US policy to prevent a coup. After learning of the bloody execution of Diệm, a shaken Kennedy actually left the room, later penning a memo in which he blamed himself for approving Cable 243). Moving on to domestic politics, Johnson states they can “beat the britches off” Goldwater. Robert says they can beat any Republican because the economy is in good shape and legislation on civil rights and poverty is forthcoming, while Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (David Schramm) adds that a nuclear test ban treaty is in place and they are moving ahead of the Soviets in space, partially due to Lyndon’s oversight of NASA. Kennedy announces his intention to visit Texas to help Lyndon with disagreements between Governor Connally and Senator Yarborough, although Johnson tells him “Don’t you worry about Texas, Mr. President. I’ll handle Texas by myself.” Robert: “Isn’t that what Davy Crockett said at the Alamo?” Jack: “Or uh, words to that effect.” On November 20, John and Jackie host a judicial reception, at which John makes a joke to Pierre, who is going to Japan, that they ought to swap destinations (in reality he made this remark to Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon). Bobby has a surprise birthday party, and declares he is not traveling to Texas.

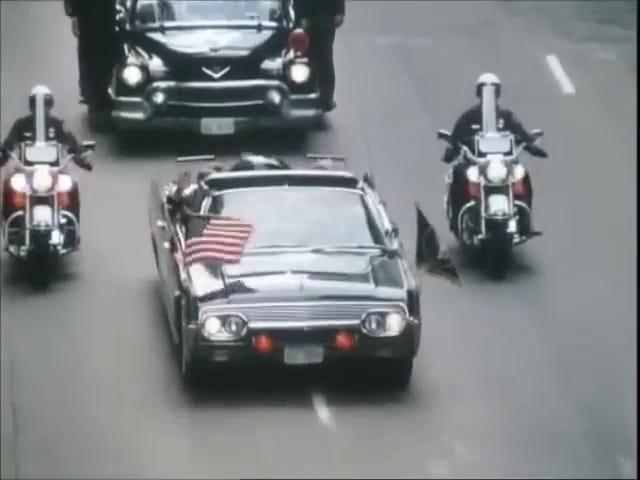

Air Force One flies to Texas. In their hotel room in Fort Worth, Jacqueline reads the speech Jack plans to deliver at the Dallas Trade Mart, particularly the part about “the watchmen on the walls of world freedom.” The next morning, flanked by Johnson, Texas Governor John Connally (J. R, Dusenberry), and Senator Ralph Yarborough (Donald Neal), John attempts to deliver a speech, although he is almost drowned out by the crowd calling for “Jackie!” They then take Air Force One to Dallas Love Field.

The final scene plays out in close to real time, beginning with a slow pan past the waiting motorcade and enthusiastic crowd (members of which hold a variety of signs, and both United States and Confederate flags, this being Texas) while we hear an assortment of quotes from John F. Kennedy, until John and Jacqueline themselves appear, being escorted by police and secret service agents, notably including Clint Hill, from the airfield to one of the lead cars, which is already occupied by Governor Connally and his wife Nellie (Margo Tully). John shakes the hands of a number of people along their route, including a group of nuns.

The motorcade continues on its way, John smiling and waving, until after a crack almost drowned out by the noise of the crowd, Jacqueline looks over to see him holding his throat.

Everything goes quiet for a moment as she leans towards him—then another shot sprays her husband’s blood across her, and the car is screaming towards the hospital, while the crowd scatters in a panic. Jacqueline, with an odd sort of shock-induced logic, climbs over the back of the car (perhaps in an attempt to retrieve a fragment of John’s skull) until Clint Hill, having run towards their car from where he was riding on the one behind, climbs in and pulls her back down into her seat.

Hill then stands over her and the fallen president, attempting to shield them with his own body, until they reach Parkland Hospital.

While the wounded Governor Connally is removed immediately, Jackie clings to John, in a cinematic Jacqueline della Pietà.

She refuses to let go of him until Hill removes his suit jacket and places it over the president’s head. President John F. Kennedy is wheeled into the hospital on a stretcher, Jackie walking alongside him, until they reach an operating theatre where the doctors begin to cut his clothes off him and do a tracheotomy and cardiac massage. A nurse attempts to keep her from entering the room, but Jackie physically grapples with her until a doctor says she has a right to be there.

Jackie tells Dave Powers to fetch a priest, then crosses herself and prays silently. She continues to watch as the doctor performing the chest compressions gives up, and the life ebbs out of her husband’s body.

The final shot of the series is a close-up of the president’s widow, reminiscent of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), blood slowly drying across her face.

This miniseries has a somewhat unusual pedigree for a show about an American president: it was co-produced by UK company Central Independent Television, now known as ITV Central, and both the director, Jim Goddard, and the screenwriter, Reginald Gadney, were English. Gadney, who also painted and wrote books (particularly thrillers), won a BAFTA for his work on Kennedy. To some extent, this award may speak as much to meticulous research as to writing, as much of the dialogue and nearly all of the incidents in the series are based on real events, although obviously with occasional liberties taken for dramatic effect. However, even in scenes without any possible historical record of the exact words spoken, the screenplay captures the personalities of the historical figures and gives a good idea of what they might have said. It also deserves credit for including almost the entirety of some of the most important speeches; rather than simply being a historical reenactment, however, these scenes generally cut to other characters watching the speeches on television, highlighting Kennedy’s place in history as the first real “television president,” and allowing commentary from a kind of Greek chorus.

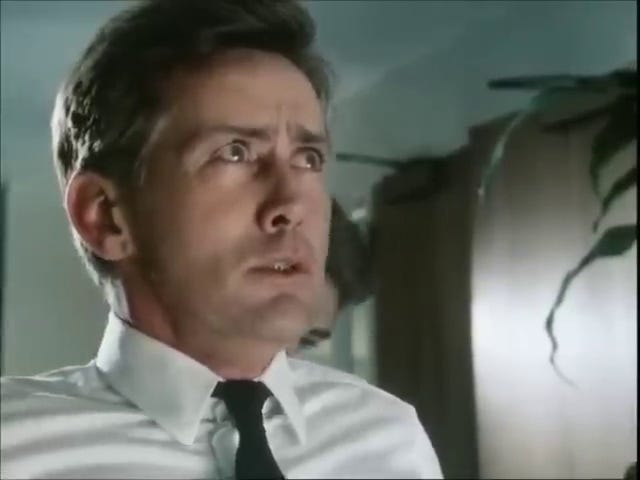

Obviously, much credit must also be given to the actors, who generally give at least solid performances all round, with some of the key players channeling their characters with almost uncanny accuracy. Obviously, the center of the show is Martin Sheen, who does an excellent job of taking on Kennedy’s mannerisms, speech patterns, and Boston accent. (The accent in fact may seem a bit too strong at first, but this may be due to Sheen’s voice naturally being higher than the real John Kennedy’s, and thus sounding slightly more nasal; one grows used to it after an episode or two). Beyond the surface level, though, Sheen gets at Kennedy as a person perhaps more than even William Devane in The Missiles of October (who resembles him more physically and vocally). Sheen’s Kennedy is a bundle of contradictions, as the real man was: possessed of a seemingly effortless charm and a public image of a picture-perfect family life, but in private battling with back problems (and Addison’s disease, though the latter malady is not mentioned in the series), engaging in countless infidelities (though this series mostly focuses on one, which is kept offscreen), and suffering the losses of multiple children. As a leader, he comes across as both intelligent and strong-willed; some may accuse the series of lionizing him too much, particularly by portraying both John and Robert Kennedy as more in favor of civil rights that they actually were early in the administration, although both grew more supportive of the cause over Kennedy’s three years in office. It is probably accurate, however, in portraying his major misstep of the Bay of Pigs as essentially the product of CIA dishonesty about whether an invasion would succeed without American military involvement. It also suggests that had Kennedy lived, he would not have escalated the War in Vietnam to the extent Johnson did, as he is portrayed worrying that Vietnam will become “another Cuba”; what would have happened is ultimately an open question, but considering his decision not to send American troops during the Bay of Pigs, this argument seems plausible. On the more positive side, Kennedy did handle the Cuban Missile Crisis well, and I particularly like how much he stuck it to U.S. Steel for the owners’ greed.

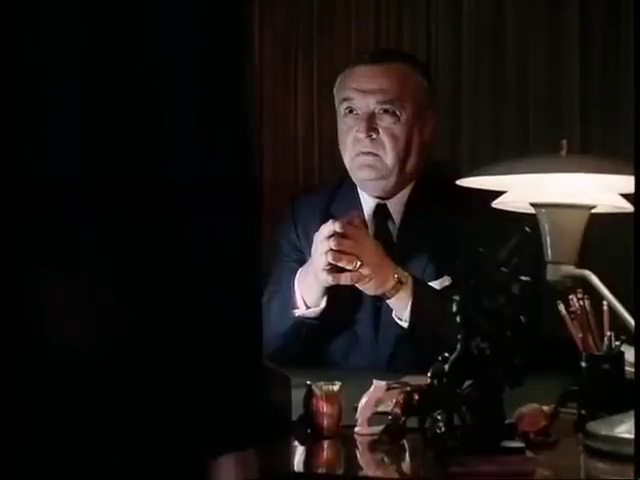

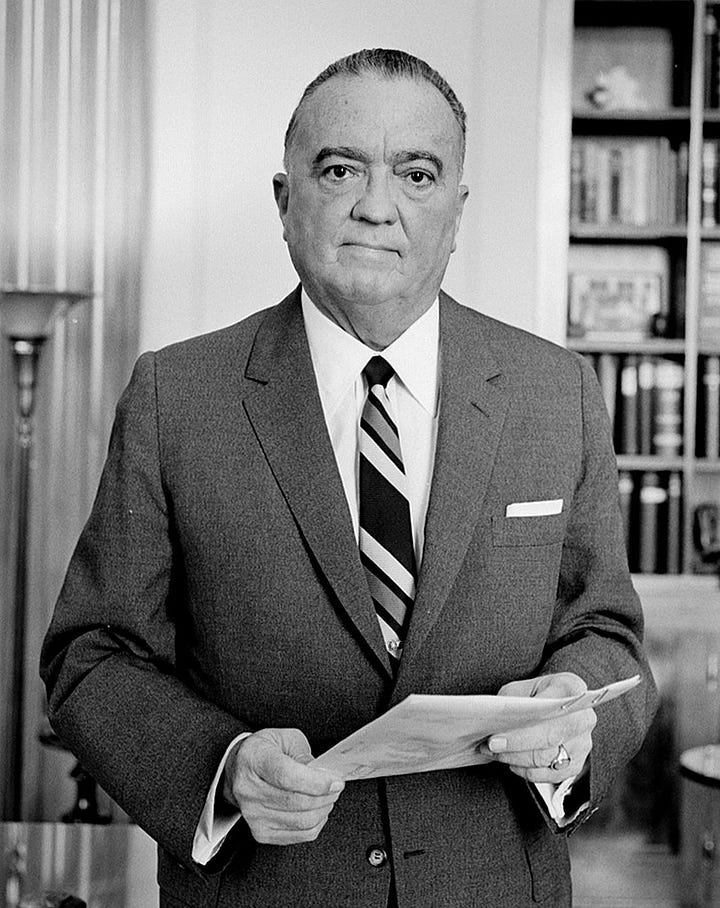

Another stand-out performance is Vincent Gardenia as J. Edgar Hoover. Gardenia’s Hoover is generally quiet, slow-moving, and affectedly careful, emphasizing to his subordinates (almost all of whom he addresses simply as “boy”) the importance of the smallest details, and ordering such things as an in-depth analysis of the meaning of the word “rendezvous” in phone calls between John and his mistress. Sprinkled throughout are also references to the rumours about his sexuality; this subtext is made text early on in the series, when Joe Sr. refers to him using a homophobic slur. Although such stories are hard to confirm, particularly as Hoover persecuted anyone who spread them when he was alive, he certainly had an unusually close relationship with his deputy Clyde Tolson. Beyond (or possibly related to) his sexuality, the series also has Hoover stating that he would have liked a family, but that his “best years” were given to his mother; he also specifically tells his deputies to call their mothers at the time of the Mother’s Day bus attacks. These are references to the fact that Hoover lived with his mother until his forties! (Perhaps he believed that a boy’s best friend is his mother). Aside from his personal life, the series gives a relatively accurate glimpse into how Hoover operated, generally through a combination of surveillance and blackmail, as well as noting his denial of the existence of organized crime (which has been suggested to be because powerful mobsters either had blackmail material on his relationship with Tolson, or because they passed him horse racing tips).

The anchor of the series, however, is Blair Brown as Jacqueline Kennedy. Although she is not directly involved in many of the important political and geopolitical events, her scenes with John humanize him even more, as she comforts him when he needs it, and at other times makes him laugh with her keen wit (which she generally tempered in public, projecting a softer, less “threatening” image to a society which is even today wary of female intelligence). The scenes which focus on her specifically, often in the company of William Walton, also provide nice bits of relief during the tenser portions of the drama. Brown gets a chance to really act in the last episode, however, managing to portray first panic, then admixed grief and strength of will with just a look; she is also clearly not afraid of looking disgusting, allowing snot and tears to mingle with the blood on her face after the assassination. It is that face which will likely remain in the viewer’s memory long after the haunting final shot has faded away.