Matewan (1987): Prelude to America’s Forgotten Battle

A bit more than a century ago, the coal fields of southern West Virginia were the epicenter of a conflict between miners and coal companies which culminated in the largest battle in the United States since the first American Civil War. It had some issues in common with that earlier conflict as well; one of the justifications, beyond its moral iniquity, for the abolition of slavery put forward before the Civil War (including by Abraham Lincoln) was that it took jobs from free labourers. A fictionalized version of the events which led to this important but mostly forgotten chapter of American and West Virginia history is portrayed in independent director John Sayles’s Matewan.

This film opens with a scene depicting the harsh realities of coal mining, introducing one of the main viewpoint characters, fifteen-year-old Danny Radnor (Will Oldham). Narration by an elderly Danny explains the tensions between the Stone Mountain Coal Company and miners who wanted a union, and that the miners called for outside assistance. This aid comes in the person of United Mine Workers (UMW) organizer (and former IWW member or “Wobbly”) Joe Kenehan (Chris Cooper). Kenehan’s introduction to the area is seeing black men brought in by the coal company to replace the unionized workers being beaten by a mob of white miners as soon as they attempt to leave the train. Once he makes it into town proper, Kenehan lodges with Danny’s widowed mother Elma (Mary McDonnell), eventually becoming a surrogate father figure to Danny, who is a gifted preacher. However, a pair of Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency men, Bill Hickey (Kevin Tighe) and Harry Griggs (Gordon Clapp) in the pay of the coal companies also arrive in town after being tipped off to Kenehan’s presence by C. E. Lively (Bob Gunton), a union member and restaurant owner who was secretly a spy for the Baldwin-Felts agency. This sets the stage for further escalation, as Kenehan tries to knit the “hillbillies,” Italian immigrants, and blacks led by “Few Clothes” Johnson (James Earl Jones, voice of Darth Vader) into “one big union,” while the detectives harass, terrorize, and even kill union miners. At the same time, which side the soda fountain/jewelry store owner and Mayor of Matewan Cabell Testerman (Josh Mostel) and his Chief of Police “Smilin’” Sid Hatfield (David Strathairn), a member of the Hatfield clan that infamously feuded with the McCoys in the middle of the previous century, will take remains an open question. (The film blends fact with fiction; while most of the central characters are fictional, C. E. Lively, Cabell Testerman, and Sid Hatfield were real historical figures).

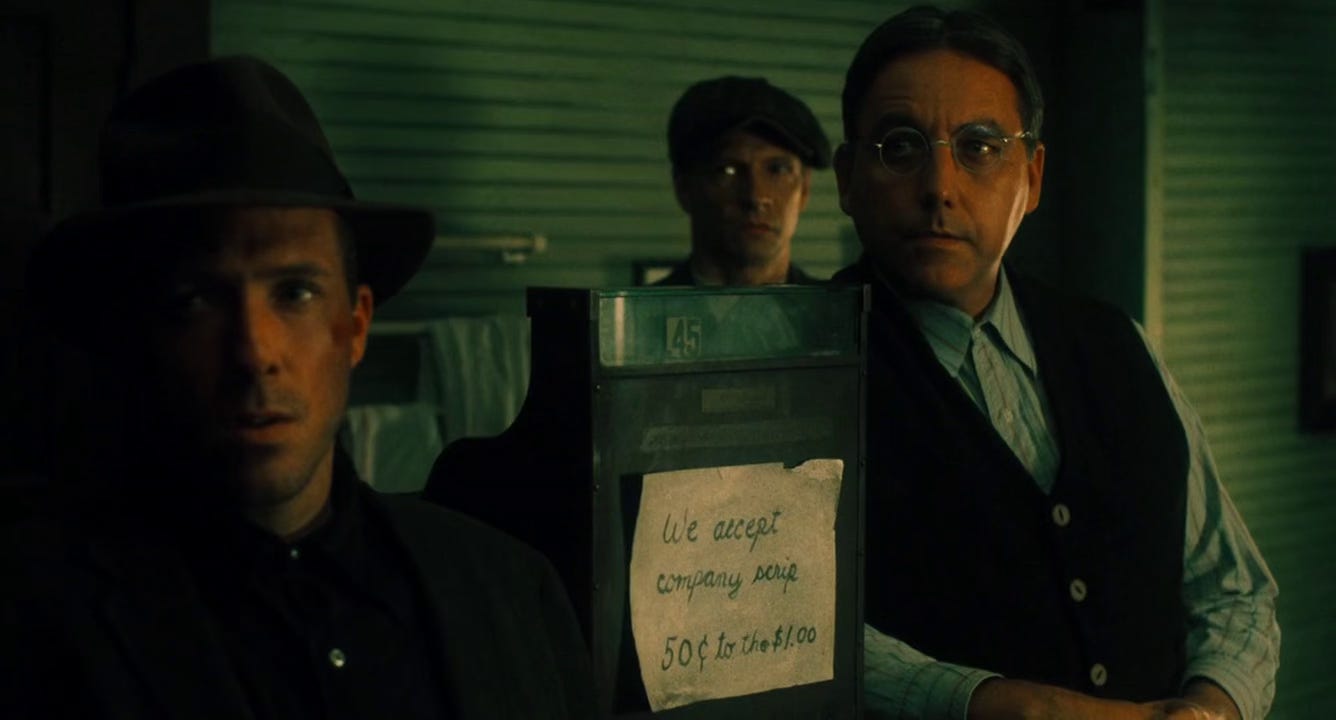

Matewan takes place during perhaps the grimmest chapter of the American labour movement’s history, when the more radical IWW was being cracked down on by business organizations, the Justice Department, the vigilante Knights of Liberty, the fascist-leaning American Legion, and even the more business-like trade union, the American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.), leaving the AFL as the only national union federation standing (Rick Fantasia & Kim Voss, Hard Work, 2004, p. 52). A scene in which a Stone Mountain Coal Company boss explains the terms of employment to the newly-arrived black miners highlights the exploitative labour conditions faced by mine workers of this era: they are paid not with money, but with company scrip usable only at the company store and occasionally, at a terrible exchange rate, elsewhere (such as Lively’s restaurant). Additionally, the costs of mining equipment (such as picks, shovels, explosives, lamps, and helmets), housing, the company doctor, and even the train ride to Matewan are deducted from their pay, putting them in a hole of debt which they must literally dig themselves out of. Protests of these harsh terms were prevented by forcing miners to sign “yellow-dog” contracts which allowed companies to fire them if they joined a union.

Matewan depicts many of the West Virginian miners as racist; they often refer to the miners imported by Stone Mountain using racial slurs. However, Joe Kenehan manages to convince them to allow the Italians and blacks into the union, a reflection of the real-life IWW’s gender and racial inclusivity. He does this not with a high-minded appeal to common humanity, but with a clear economic argument: that the coal company uses its workers like machines and doesn’t care what color they are, and that racial and ethnic tensions distract from the fact that there are only two sides in this struggle: “Them that work, and them that don’t.” Thus, the only way to make the company change its policies is to stop all mining by convincing the imported miners to strike as well. Kenehan manages to bring the Italians on board by convincing their de facto leader Fausto (Joe Grifasi) to join the “sindicato,” while Few Clothes comes to the union gathering on his own steam, stating that he’d “never been called no scab—and I ain’t fixin’ to start up now.” Once all three groups are officially on strike and set up a camp together, the mistrust between them starts to dissipate, shown by such details as Mrs. Elkins (Jo Henderson), mother of Danny’s friend Hillard (Jace Alexander), initially thinking Fausto’s wife Rosaria (Maggie Renzi, Sayles’s partner) has an “evil eye” and criticizing her cooking, but later giving her a rabbit, navy beans, and ramps so that her children won’t go hungry. The increasing spirit of camaraderie is also shown through music. Early in the film, the three groups are heard playing different musical styles, with a pair of hillbilly musicians being annoyed by the Italian folk music. In the camp, however, they harmonize, combining Appalachian fiddle and guitar, Italian lute, and blues harmonica.

Another major element of the film is religion. Religion is often thought of as a bulwark for the establishment (or to quote Karl Marx, the “opium of the people”, meaning a temporary alleviation of their suffering). Particularly in recent times, the American left has often been squeamish about using religious arguments to motivate people to take political action. However, every major American social reform movement has had some religious backing, although admittedly religious groups have been more central to some movements (such as abolition and civil rights) than others (feminism, queer rights). Matewan depicts religion in a nuanced manner, with the pulpit being used to deliver both pro- and anti-labour messages, depending on who is speaking from it. It appears first as an anti-labour and pro-capitalist force, with the preacher at a “Hard Shell” Baptist church (played, in a Hitchcockian move, by director Sayles himself) declaring that Beelzebub walks the earth as “Bolshevik, socialist, communist, union man!” However, immediately after this, Danny preaches from the same pulpit, retelling Jesus’ parable of the labourers in the vineyard (Matthew 20:1-16), but concluding that if Jesus saw the unfair treatment of workers by the coal company, he would change his opinion. With this blending of Christianity and left-wing politics, he prefigures the liberation theology developed in Latin America in the 1960’s. Although Kenehan does not express any personal religious belief, he speaks respectfully of the pacifist Mennonites’ commitment to their beliefs, even in the face of essentially torturous treatment, which he witnessed when both he and they were locked up in Leavenworth Prison for refusing to fight in the Great War. The most anti-religious characters in the film are in fact the two detectives Hickey and Griggs, who chortle about how little of the Bible they have read and then launch into a mocking rendition of “There Is Power in the Blood,” followed immediately by a cut to the “soft shell” congregation earnestly singing the same hymn. (Interestingly, this tune was also repurposed by IWW musician Joe Hill as “There Is Power in a Union”—not to be confused with the Billy Bragg song of the same name set to the tune of “Battle Cry of Freedom”). Hickey and Griggs spend most of this service drunkenly laughing together at the back of the church, not realizing that Danny is using another Bible story, this time Joseph and Potiphar’s wife (Genesis 39), to warn the miners of the Baldwin-Felts agents’ scheme to use false rape accusations to make them kill Joseph Kenehan.

Joe is shown as being averse to the use of violence, but this is less due to any specifically pacifist ideology than a matter of pragmatism and tactics. His explanation of why he refused to fight in the Great War is that it was a war in which the rich made the poor fight for them, and he felt he had more in common with soldiers on the other side than with the politicians and generals giving orders. His opposition to violence in the case of their struggle against the coal company, by contrast, seems to be because he knows that as good of shots and as many guns as the miners have, if they start a private war against the company’s gun thugs, the government will intervene on the side of the capitalists. However, Kenehan is ultimately unable to prevent violence. The pent-up tensions finally explode into a shootout at the climax of the film, a relatively historically accurate depiction of the Battle of Matewan, which occurred exactly 105 years ago, on May 19, 1920. (It was also known as the Massacre at Matewan, although the detectives were actually massacred more than the miners). This spark of violence would inflame even more bloodshed, culminating in the Battle of Blair Mountain, the conclusion of which would prove Joe Kenehan’s prediction about government intervention mostly right.