The Book of Lost Tales, Vols. I & II by J.R.R. Tolkien: The First Draft of Middle-Earth

Most readers’ introduction to John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s writings about Middle-Earth [the name of which is itself a literal English translation of Old Norse Miðgarðr or Midgard] is from the novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. After reading those books, many newly minted Tolkien fans attempt to read the Silmarillion, the first Middle-Earth book released by Tolkien’s son Christopher after his father’s death, and are stopped cold by an imposingly dense work heavy on unfamiliar names and broad historical and mythic arcs (to the extent that it is frequently compared to the Bible), but relatively sparse on the details of setting and character that Tolkien’s novels feature. The next Middle-Earth book after this, Unfinished Tales, is—true to its name—a collection of uncompleted fragments, which besides being by definition somewhat narratively unsatisfying, usually require knowledge of the Silmarillion for proper context.

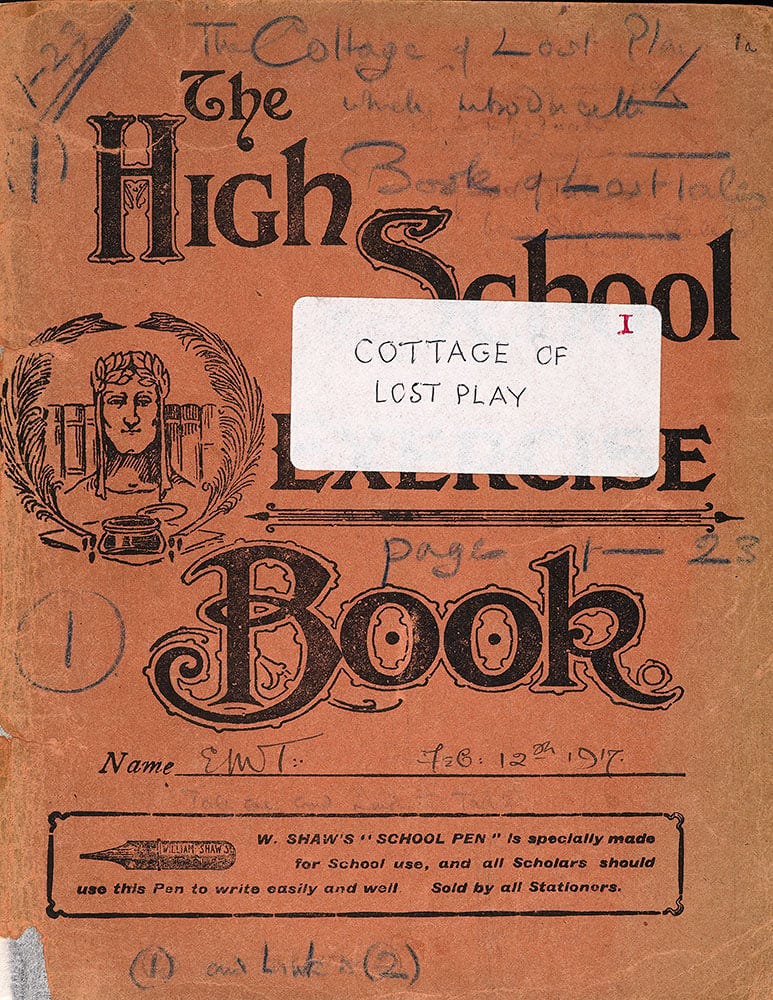

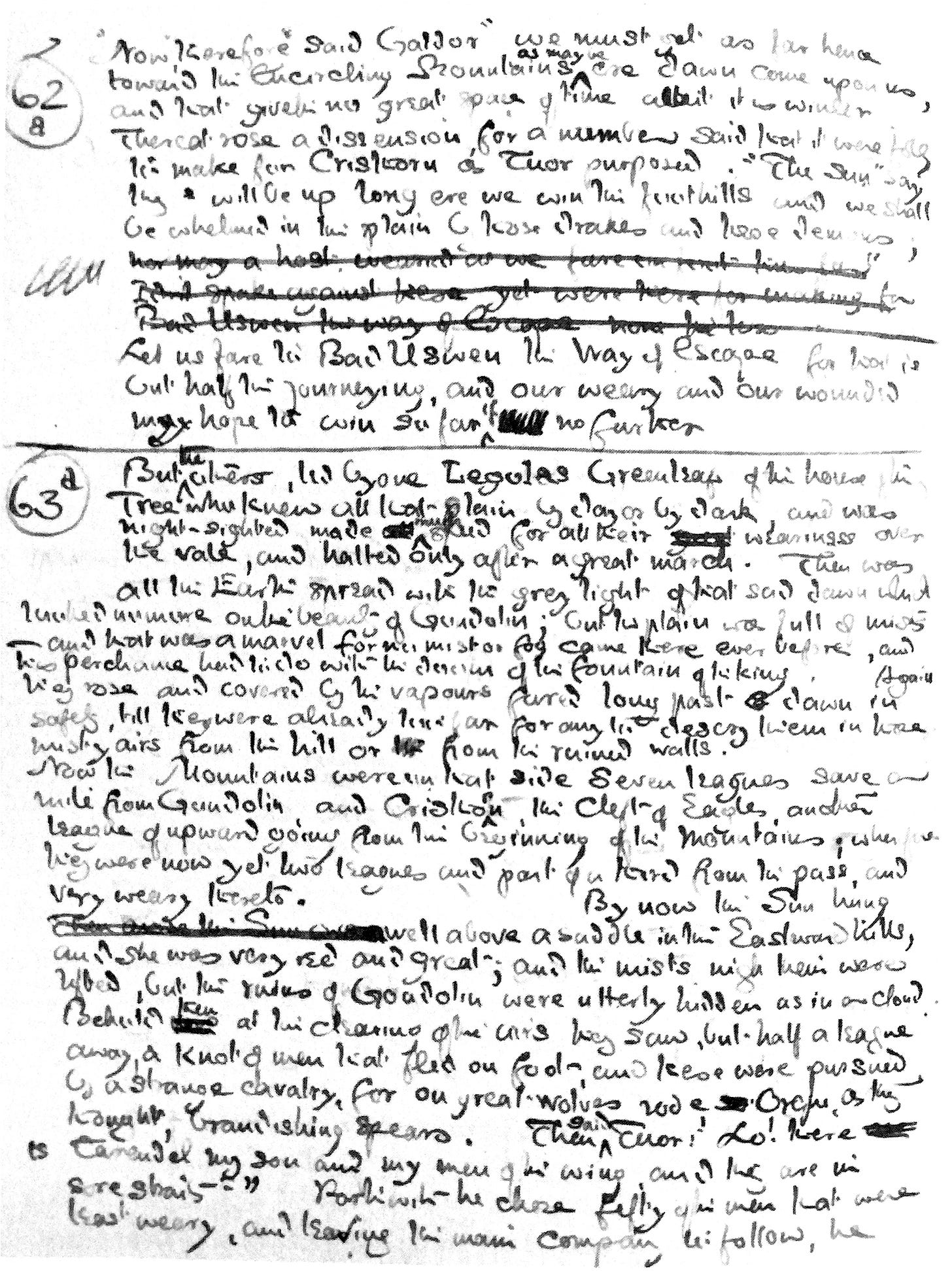

A better place to begin exploring the broader Middle-Earth narrative might be at the beginning not just of the fictitious history, but of Tolkien’s creative process. The Book of Lost Tales, published in two medium-sized (compared to the Silmarillion) volumes compiled by Christopher Tolkien, who also wrote extensive explanatory material for them, comprise many of Tolkien’s earliest writings about Middle-Earth. Despite being early drafts, with much confusion in names and words and shifting of elements in the “history,” and despite not being “canonical” to the novels, Lost Tales is perhaps more approachable than the much revised and condensed Silmarillion or the scattered Unfinished Tales, as it is primarily a collection of largely complete and fully (or at least mostly) fleshed-out stories.

Additionally, when these narratives are placed in the context of the period when they were written, facets of them that seem relatively minor when seen in the context of the late-twentieth century suddenly gain an immediacy and historical relevance. Tolkien did not come to these particular ideas in a vacuum, or out of idle fancy. While Tolkien’s creation of his secondary world is often thought of primarily as an outgrowth of his linguistic experimentation (which is partially true), Tolkien’s psychological impetus for its creation, which the publication dates of The Hobbit between the World Wars and The Lord of the Rings after them may have partially obscured, becomes far clearer. Many of the key themes of these stories were borne out of Tolkien’s twin desires to return to England and to his wife while serving in World War I; in fact, his earliest writings on Middle-Earth and related concepts derive from poems and other pieces composed in British Army field hospitals where Tolkien was recuperating from trench fever spread by the rampant lice that preyed on soldiers on the Western Front. In a time when he was either abroad or continually ill, Tolkien created an idealized type of England in his mind to substitute for the real one which was, in one way or another, denied to him. Later, while on home front duty during his convalescence, an incident in which Tolkien’s wife, Edith (née Bratt) , danced in a hemlock grove inspired the character of elf-princess Lúthien, and the recurrent theme of love between man and Elf-maid.

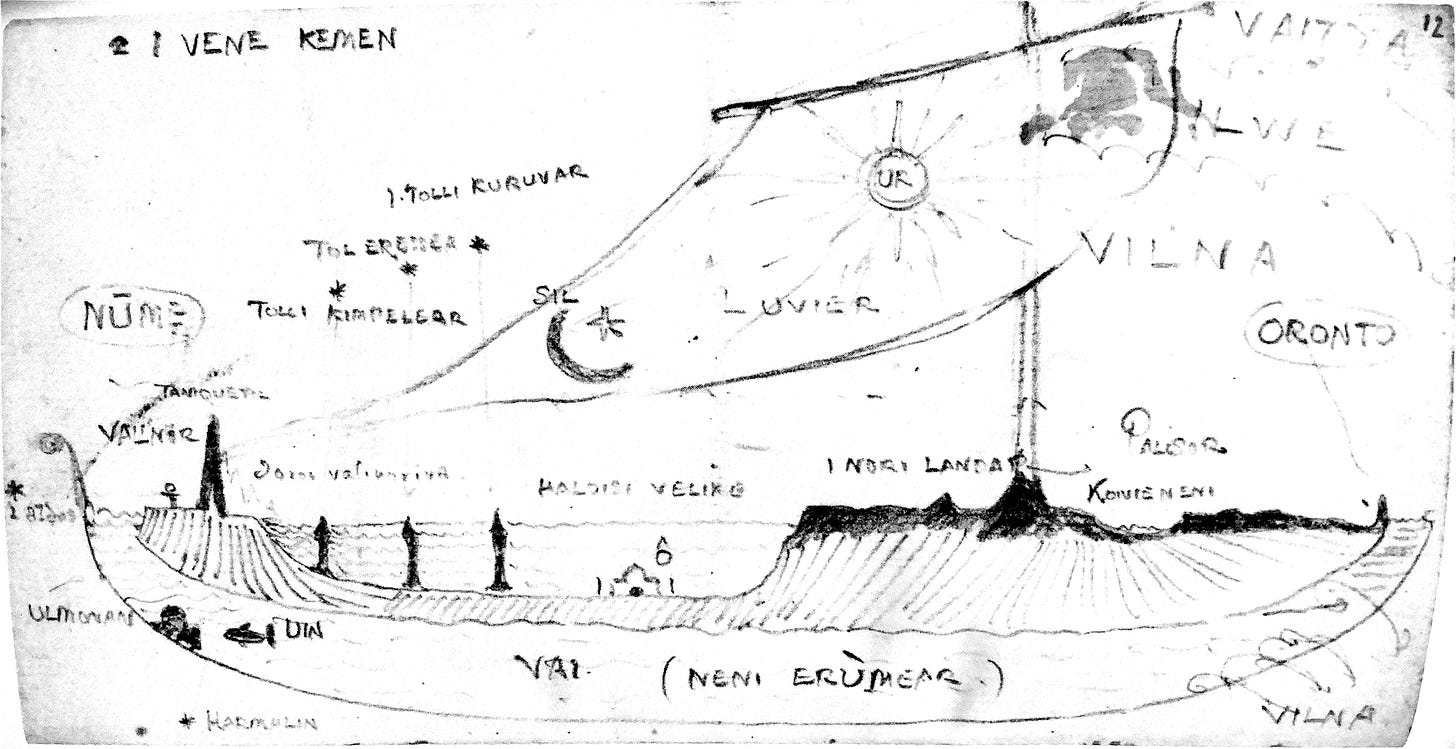

Another of Tolkien’s purposes in creating Middle-Earth was to produce a coherent and specifically English/Anglo-Saxon mythology on par with the Norse Eddas or Finnish Kalevala. All of the stories within The Book of Lost Tales are embedded within a frame story about a mariner named Eriol/Ottor Wæfre (wæfre=wayfarer in Old English; he was renamed Ælfwine=Elf-friend in later writings) who travels to the land of the Elves, Tol Eressëa, and learns their history in a place called the Cottage of Lost Play. In earlier versions of the conclusion of this story, Tol Eressëa is invaded by other men and becomes the modern British isles, and the Anglo-Saxons are posited as Eriol’s people, with Hengest and Horsa as his sons, thus giving them a “right” to the land which other men such as the Celts and Romans lack. In later versions, Ælfwine is an Anglo-Saxon from Wessex in England, which Tol Eressëa is west of; but the Elves inform him that England was formerly inhabited by the Elves, who called it Luthany. Thus, an Elvish connection to England is maintained, but attenuated in the later story.

This somewhat colonialist justification for the Anglo-Saxon “invasion” of England (as Tolkien thought of it, following the lead of Victorian historians, though there is little reason to believe the Anglo-Saxon migration was a specifically military venture!), and establishment that the English have the “true” tradition of elves is interesting. However, it was to disappear (probably for the better) as Tolkien moved his history further back into the mists of time, eventually removing almost all references to actual history, and also made more of a break with the then-current English conception of elves and faeries (the terms were used fairly interchangeably even by Tolkien then) as diminutive, diaphanous, and unbearably cutesy.

Many of the stories themselves would remain fairly constant in broad narrative terms, though changes of detail and complications or simplifications of structure occurred between the earliest and latest versions of them. Nevertheless, stories such as the creation of Middle-Earth, Beren and Lúthien, Túrin and the Dragon, and the Fall of Gondolin would retain many of their core elements until the latest versions given in the Silmarillion. On the other hand, some elements which were much reduced later include the chain of events leading to the creation of the Sun and the Moon, and the very tactilely described forging of those heavenly bodies. However, all the stories display both a more deliberately archaic style than Tolkien would generally adopt later (rather reminiscent of Edmund Spenser’s similar archaicism in The Faerie Queene, despite Tolkien’s dislike of allegory) and a primitiveness of the details, for instance in characters who are great and wealthy Elf-kings in later tellings being depicted as sometimes petty and greedy lords hoveling in caves in these stories. The Elves, in particular, would gain much physical and moral stature, and far greater wisdom, in later writings.

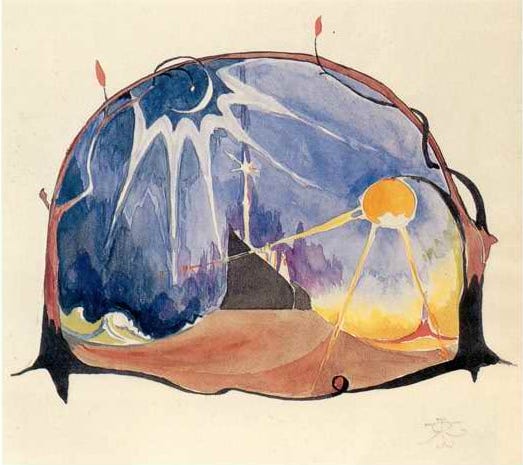

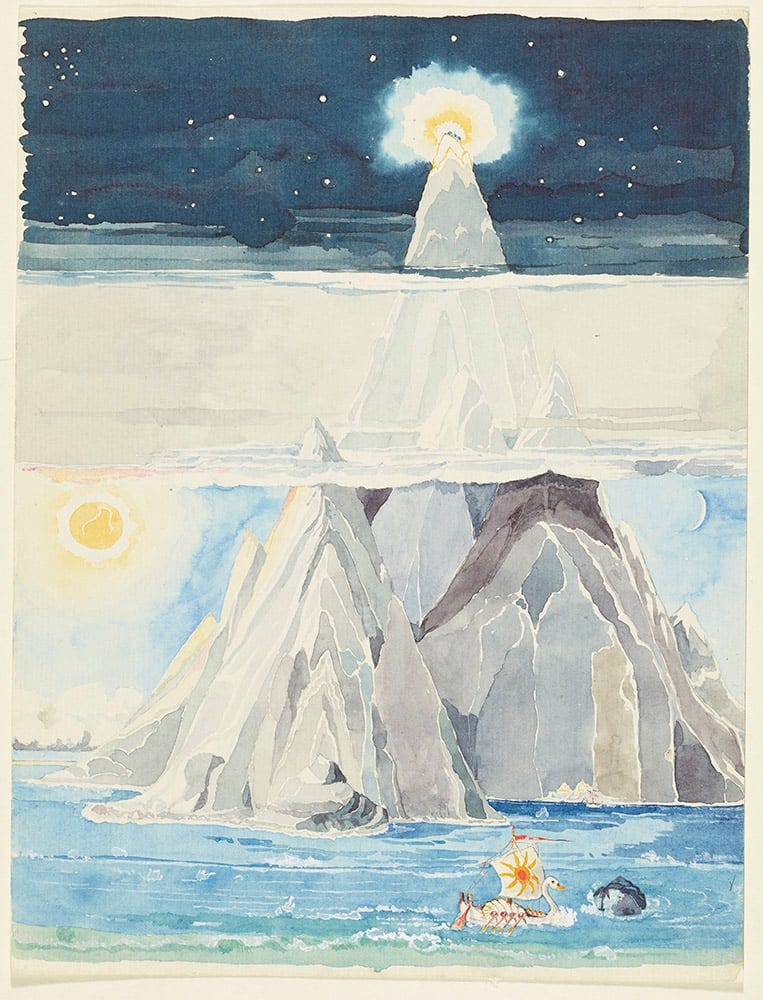

Tolkien’s version of the creation myth is interestingly musical in its conception, with the world of Arda (which Middle-Earth lies upon) described as the product of the melodies and harmonies sung by the Ainur, who are something of a cross between gods in the Greco-Roman or Norse traditions, and some Judeo-Christian ideas about angels, and are the first beings created by the omnipotent God figure, Ilúvatar. Some of the Ainur then enter the world they had created and became the Valar. Most of the rest of the first volume of Lost Tales concerns the dealings of the Valar, most of whom are less petty than the above-mentioned pagan gods; however, one of them, Melko/Melkor, is the legendarium’s Satan analogue, who attempts to undo or spoil the works of the others, and is eventually bound in chains for his crimes. However, Melkor inevitably escapes, and with the help of giant spider-like being Ungoliont, destroys the twin trees that give light to the world; he also steals gems called Silmarils wrought by the Elves, causing some of them to abandon their first city of Kôr in Valinor (land of the gods) and pursue him to Middle-Earth, though not before they have shed the blood of another group of Elves.

The second and slightly longer volume of Lost Tales focuses less on a broad mythic arc and more on the stories of individual characters, such as the love and trials of Beren and Lúthien Tinúviel, who stole one of the Silmarils from Melko’s crown and then cheated death in a manner reminiscent of Orpheus (it should be noted that Tolkien did a translation of the Middle English lay Sir Orfeo). Oddly, in the earliest extant writings, Beren Ermabwed [One-handed] is an Elf, but this is a revision from a now lost or written-over text in which he was a man, which he would become again; his status as a man would in fact form the central motif of mortal human and immortal Elf-maid who gives up her immortality, an idea so powerful that it would impose itself onto The Lord of the Rings via the Aragorn/Arwen relationship, quite against Tolkien’s original plan to have Aragorn marry Éowyn. This story also features the first appearance of the character that would evolve into Sauron: Tevildo, Prince of Cats (Beren and Lúthien are aided by Huan, Captain of Dogs). By the next version, cat and dog antagonism would disappear from the story as Tevildo had become Thû, Lord of Werewolves.

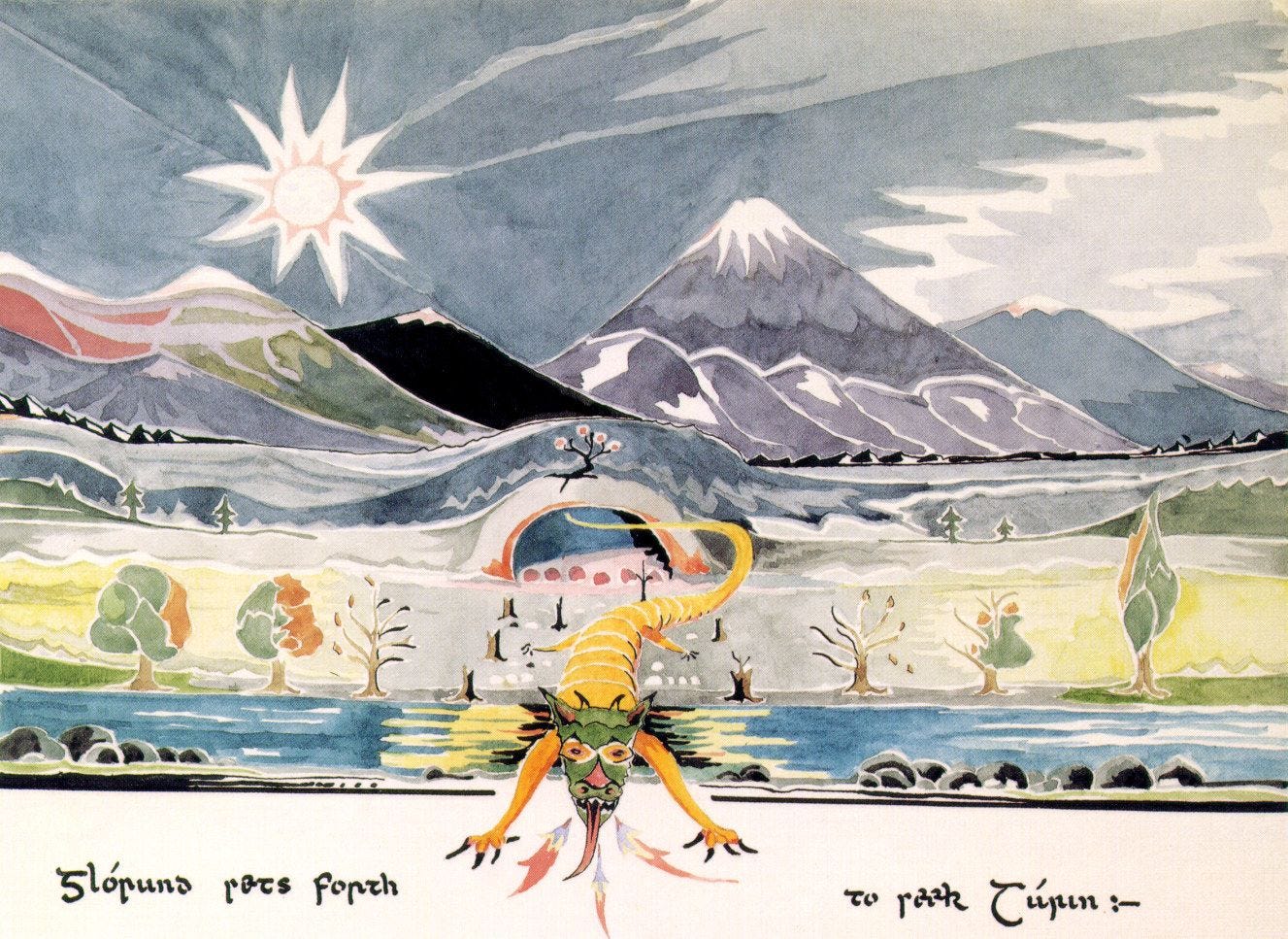

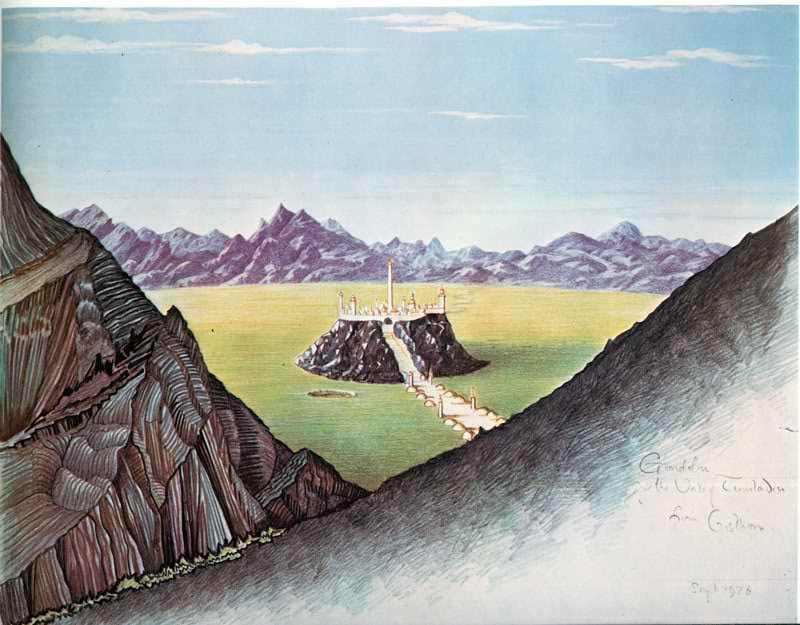

The other stories include the tragic tale of cursed hero Túrin Turambar, who unwittingly married his sister Nienóri (shades of Oedipus Rex) and slew the Foalókë [dragon or worm] Glorund; the fall of the mountain-ringéd hidden Elvish city Gondolin, in which the name Legolas first appears; and the tale of the Nauglafring, or Necklace of the Dwarves, a story of treachery and bloodshed caused by lust for treasure which helps explain the antagonism between elves and dwarves. After this, the book trails off into fragments and sketchy outlines of the tale of Eärendel the mariner, who sailed into the sky with a Silmaril, becoming a star; this story has as its seed a line of the Anglo-Saxon poetry known as Crist I. The last section deals with the planned connection of the mythic cycle back to the history of Eriol/Ottor Wæfre, culminating with the end of his story; however, Tolkien abandoned work on these particular prose versions of the story before he wrote this part, or much of Eärendel, instead choosing to focus on poetic versions of Lúthien and Túrin.

The Book of Lost Tales, Vols. I & II throw a great deal of illumination on both Tolkien’s impetus and inspiration for his Middle-Earth legendarium. For those who are familiar with the Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales, Lost Tales provides a fascinating glimpse into Tolkien’s first conception of Middle-Earth. Despite some areas that are rather heavily annotated, it also provides a place to begin exploring the deeper mythology in a relatively more approachable manner than those larger and more difficult tomes. For all readers, it reveals the origin of many concepts which were to become iconic, even integral, parts of the modern fantasy genre.