Selma (2014): The Power of Peaceful Protest

Sixty years ago this month, Americans from multiple walks of life came to Selma, Alabama to peacefully protest the racial injustice of our society. They were met with violence and brutality, the televised images of which shocked the conscience of the nation and galvanized the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Almost fifty years later, director Ava DuVernay chronicled these events in her powerful film Selma (2014).

While not strictly a biopic, Selma’s central figure is the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (played by British-Nigerian actor David Oyelowo, because no one can play American historical figures as well as Brits). Oyelowo looks, sounds, and acts so much like the real Dr. King in this film that if it were released today, it might raise suspicions that there was some sort of face-swapping AI reshaping his features in post-production; but no, he really is that good of an actor. The film begins in a relatively standard biopic style with King accepting a Nobel Peace Prize, after being reassured about his speech by his wife Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo, another Brit).

Less than five minutes in, though, DuVernay shows the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing; it begins in real-time, but the camera then lingers on a slow-motion shot of embers, dust, rubble, and then a girl’s dress and legs as she is thrown through the air by the force of the blast. Although the Birmingham bombing actually took place in 1963, the year before King received the Nobel, and about a year and a half before the Selma marches, the event’s placement in the film effectively demonstrates the violence with which segregationists in the South were willing to defend their racial stratification of society. Violence, often at the hands of various police forces, and the civil rights activists’ determination and persistence in the face of it, are major themes of the film. DuVernay’s clear portrayal of it makes what could have been a slow, talky film feel dynamic, kinetic, and urgent.

The film continues to broaden its scope, from spotlighting the personal struggle of Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey, proving she can still act despite being better known as a talk show host), who becomes the everywoman counterpart to the famous historical figures, being denied her right to vote; to setting scenes the inner sanctum of American democracy, the White House, where King meets with President Lyndon Baines Johnson (English actor Tom Wilkinson). Later, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker, Dr. Curt Connors in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man films) suggests dirty tricks to tarnish King to Johnson. (In reality, it should be noted that Hoover never requested permission for surveillance from Johnson, having tacitly been allowed to surveil King by Robert F. Kennedy during the previous administration, and seldom having many scruples about carrying out illegal and unethical actions without presidential approval).

The film truly reveals itself to be an ensemble piece when MLK Jr. travels to Selma, Alabama in a car full of civil rights activists, specifically Ralph Abernathy (Colman Domingo), Diane Nash (Tessa Thompson), Andrew Young (André Holland), and James “Shackdaddy” Orange (Omar Dorsey).

Once in Selma, King speaks at Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, kicking off a voting registration campaign. Members of King’s group the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) lead mass voter registration efforts, but are blocked by police under the command of Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark (Stan Houston).

Although the movement tries to be nonviolent, at one point Annie Lee Cooper punches Sheriff Clark (to stop him from striking someone else in the film, and as a reaction to his twisting her arm in real life), and is then beaten herself. King is also arrested some days later, while Governor George Wallace (English actor Tim Roth, doing a decent southern accent) gives a speech in which he refuses to allow continuance of the “disturbance” and accuses liberals and progressives of seeking to make separate races into “one mongrel unit” (touching on southerners’ ever-present fear of miscegenation).

The situation escalates even more when state troopers led by Alabama Highway Patrol head Al Lingo (Stephen Root) violently disrupt a night march. One of the marchers, young Baptist church deacon Jimmie Lee Jackson (LaKeith Stanfield), his mother Viola Jackson (Charity Jordan), and his grandfather Cager Lee (Henry G. Sanders) attempt to take refuge in a diner called Mack’s Café, pretending to be customers, but troopers follow them in. They beat Jimmie, and one of them shoots him twice; he dies eight days later in hospital, of infection in his wounds. King speaks at one of the memorial services for Jimmie Lee Jackson.

The SCLC moves forward with plans to have a march from Selma to Montgomery. King does not attend the first march, but despite doubt within his own organization, SNCC member (and future congressman) John Lewis (Stephan James) participates, as do Hosea Williams (Wendell Pierce) and Amelia Boynton Robinson (Lorraine Toussaint). On Sunday, March 7, 1965, more than 500 protestors leave Selma and arrive at the Edmund Pettus Bridge (named after Confederate brigadier-general, US senator, and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan Edmund Pettus), only to find their way blocked by a line of state troopers. The commanding officer of the troopers, Major John Cloud (Michael Papajohn, best known as Uncle Ben’s alleged killer in Spider-Man), orders the marchers to disperse.

When they refuse to, the troopers attack, putting on gas masks before attacking with truncheons and tear gas, even clubbing and whipping people from horseback. Interspersed with the violence itself are the reactions of those watching it, in person or from afar; a group of southerners with confederate flags and signs bearing racist slogans cheer it on, while King and his associates, President Johnson himself, and most of the ordinary citizens watching the event on television are shocked by the level of brutality. Also shown is Governor Wallace, who seems more pensive than anything else.

In the aftermath of “Bloody Sunday,” the SCLC calls for another march on Tuesday, March 9. However, after attorney Fred Gray (Cuba Gooding Jr.) attempts to get a court order to prevent further police interference, Judge Frank Minis Johnson (Martin Sheen in an uncredited role) instead issues a restraining order, and Johnson sends Assistant Attorney General John Doar (Alessandro Nivola) to ask King to postpone the march. King agrees not to cross the bridge, but the activists decide they must make a symbolic gesture on Tuesday. The second march comprises around 2500 people, including a sizable proportion of whites and participation by clergy of numerous denominations, including Catholic nuns, Jews, Unitarian Universalist ministers, and Greek Orthodox Archbishop Iakovos (Michael Shikany). However, after leading the demonstrators onto the bridge and kneeling in prayer, King turns around and leads them back into Selma. This leads some marchers to criticize him, and this event to be dubbed “Turnaround Tuesday.”

Despite avoiding the sort of mass violence that occurred two days prior, several of the Unitarian ministers are attacked by racist thugs later that night, with one of them, Bostonian clergyman James Reeb (Jeremy Strong) dying two days later.

President Johnson and King have a tense phone conversation, with Johnson angered at demonstrations that occurred within the White House, while King tells Johnson that he has the power to end the protests and the violence by acting. King, discouraged by Johnson’s lack of movement, talks to John Lewis, who tells him about the violence he faced during the Freedom Rides and repeats the words King said years back, that they have “come far to turn back now.” King is surprised to encounter his wife Coretta in the courthouse, where Judge Johnson rules that they have a First Amendment right to peacefully demonstrate by marching, especially given the enormity of the injustice they are protesting.

Through the efforts of Bayard Rustin (Ruben Santiago-Hudson), a number of prominent entertainers, including Nina Simone, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez, and Peter, Paul, and Mary agree to perform at a “Stars for Freedom” concert. At a meeting in the White House, President Johnson chastises Governor Wallace for focusing too much on the “black issue,” reminding Wallace that he campaigned for governor on the platform of helping the poor. Furthermore, Johnson accuses Wallace of not seeing the bigger picture and tells him “I’ll be damned if I’m going to let history put me in the same place as the likes of you.” On March 15, President Lyndon Baines Johnson gives an address to a joint session of Congress in which he puts forward the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In Alabama, Martin Luther King, Jr. leads the marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and eventually to Montgomery.

On March 25, on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol (which was once the first Confederate capitol), King gives a rousing speech to a crowd of 25,000.

These last scenes are interspersed with real historical footage of the marches, and also feature text describing the fates of the various historical figures portrayed. One of them, Viola Liuzzo (Tara Ochs), would not even live to see another sunrise, as she was the victim of a drive-by shooting by Ku Klux Klan members, including an FBI informant.

Selma provides a compelling cinematic exploration of what it takes to carry out an effective mass peaceful protest. The organizers must be able to operate in multiple arenas, from maintaining the morale of their supporters, to dealing with legal issues, while making sure their actions and the optics that result from them will contribute to their ultimate political ends. Nor does the film gloss over the difficulties in uniting disparate groups to pull in the same direction; throughout the film, the younger, grassroots SNCC displays mistrust of the more nationally focused SCLC. Malcolm X (Nigél Thatch, who would reprise the role on TV show Godfather of Harlem), a much more radical civil rights figure who was not committed to King’s peaceful tactics, also makes an appearance, meeting with Coretta Scott King early in the film. However, despite his differences with Martin Luther King, he tries to assist by making himself the embodiment of the potentially violent threat that whites would face if they did not accede to King’s peaceful efforts, thereby making King look less extreme.

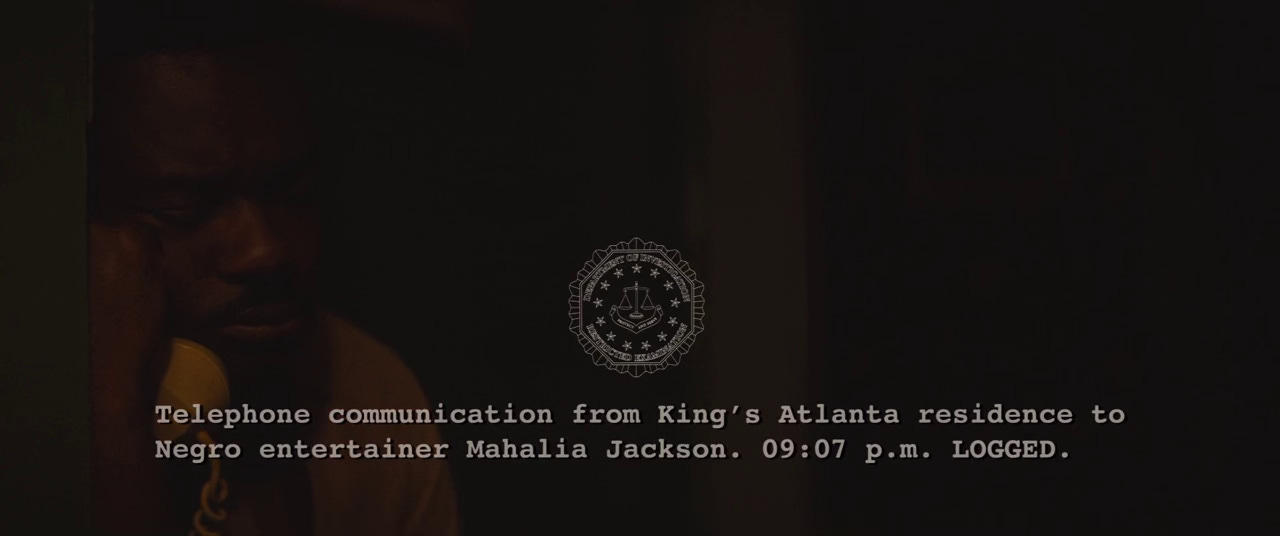

Another through line of the film is the government’s less obvious methods of trying to suppress the civil rights movement. One of the film’s most inventive techniques is that rather than simple time and location intertitles, information on place and time is delivered in the form of FBI reports on King’s movements. Early in the film, tape recordings allegedly of King with a woman other than his wife are delivered to his house; the film leaves open to interpretation whether King had extramarital affairs, but Coretta identifies this recording as fake. Both the surveillance and the tape recordings (and accompanying threatening letter) were part of the FBI’s far-reaching (and highly illegal) COINTELPRO (Counterintelligence Program), which was not exposed until the 1971 Media, Pennsylvania break-in by left-wing activists.

One of the few problems with Selma (though not one the filmmakers had control over) is the lack of Martin Luther King Jr.’s actual speeches. King’s estate had licensed the film rights to his speeches to Dreamworks and Warner Bros. for a not-yet produced project intended to have Steven Spielberg’s involvement, and Selma’s producers were unable to gain the rights for use in this film. DuVernay tries to get around this problem by writing speeches reminiscent of King’s style, but obviously this approach can never rise above the level of well-done imitation. It seems rather ridiculous to me that speeches from fifty years ago, particularly ones of such historical interest, are not in the public domain; to quote MLK himself, “capitalism has outlived its usefulness.” Aside from this problem, Selma is quite historically accurate, almost never directly contradicting the historical record, although obviously some events are compressed and details of others are invented.

Overall, Selma is a largely accurate, well-written and -directed, and powerfully performed reenactment of one of the key events in the Civil Rights movement. In this moment, sixty years on from the events portrayed, when the hard-won progress towards equality and racial justice is more threatened than it has been in decades—not just through rhetoric, but as a matter of official government policy—we would do well to study and learn from the example of the Americans of all walks of life who stood up against senseless bigotry, some even laying down their lives for the cause. Unlike when Johnson was president, protest may not change the minds of any of the current denizens of the White House, but I believe it is still important to publicly display our discontent and show that not everyone is bowing down in the face of tyranny.